One Hundred Trillion People Are Sex Trafficked Every 0.00025 Seconds — In Our Own Backyards!

The good, the bad, and the ugly of trafficking statistics

By Courtney Furlong, PhD, LPC, CRC

Sensational movies, documentaries, news programs, and creative storytelling have educated the general public and framed the narrative of our collective understanding of sex trafficking and sexual exploitation. The headlines and statistics get our attention and, so often, our dollars. In the United States, the Wayfair1 and Pizzagate2 scandals led to a country-wide demand to “Save Our Children.” But viral scandals and click-worthy headlines rarely tell the whole story. They oversimplify a deeply complex issue, reducing it to shadowy conspiracies and “stranger danger,” while ignoring the everyday realities of exploitation.

This limited perspective lacks the nuance that is critical for us to begin addressing the compounding systemic injustices that create the vulnerabilities that lead to commercial sexual exploitation. Poverty, abuse, and issues with the education and foster care systems3-4 are not as sensational as a Hollywood plot—but they are the real drivers of risk. And if our understanding starts with shaky numbers and sensational claims, our solutions will be just as fragile. Before we can fix the problem, we need to talk about why measuring trafficking is so hard—and why the numbers you see in headlines often don’t add up.

DATA AND DISTORTION (i.e., The Ugly)

Due to the covert and illegal nature of human trafficking, it is extremely difficult for governments and researchers to accurately measure the breadth and scope of the illicit sex industry.5-6 Fear and shame create additional barriers to engaging the survivor and perpetrator communities alike. Underreporting is pervasive, as survivors and perpetrators may fear retaliation, stigma, or criminalization.7 Further, a recent study suggested that 38% of survivors of commercial sexual exploitation do not have a high school diploma or GED,4 which may contribute to limited interest in research as well as literacy challenges that can affect participation. Many survivors do not speak the predominant language, adding another layer of complexity.

Ethical concerns further complicate exploitation research, including whether researchers have an obligation to report illegal activities. Institutional review boards (IRBs) tend to be highly risk-averse and often hesitate to approve studies involving vulnerable* populations. Additional barriers include housing instability,8-9 frequent changes in phone numbers, and the high mortality rate among survivors of commercial sexual exploitation,10 all of which make longitudinal data collection—data gathered across multiple time points—especially challenging.

Funding limitations create another significant obstacle.11 Research on trafficking often competes with other urgent social issues for scarce resources, leaving many studies underpowered or abandoned altogether. Even when funding is available, survivor mistrust of institutions and researchers—often rooted in past exploitation or systemic failures—can make recruitment and retention extremely difficult.12

Beyond these barriers, methodological challenges abound. Data sources are fragmented across law enforcement, non-government organizations (NGOs), and healthcare systems, which rarely share information effectively.5,13 Definitions of “human trafficking,” “sex trafficking,” and “commercial sexual exploitation” vary widely across countries, states, jurisdictions, and studies, making comparisons unreliable.14,15,16 Cultural barriers, including norms around privacy and gender roles, complicate cross-cultural research, while technological limitations—such as lack of secure communication tools or tech literacy—hinder remote or follow-up data collection.

In short, the numbers we see in headlines often rest on shaky foundations—built from incomplete data, ethical constraints, and methodological compromises. And when those shaky foundations become the basis for headlines, funding decisions, and public policy, the consequences ripple far beyond the research community.

HEADLINES AND HARM (i.e., The Bad)

When these challenges produce incomplete or inconsistent data, the consequences extend far beyond academic debates. Misleading statistics shape headlines, influence funding priorities, and drive public policy—often in ways that do more harm than good.17

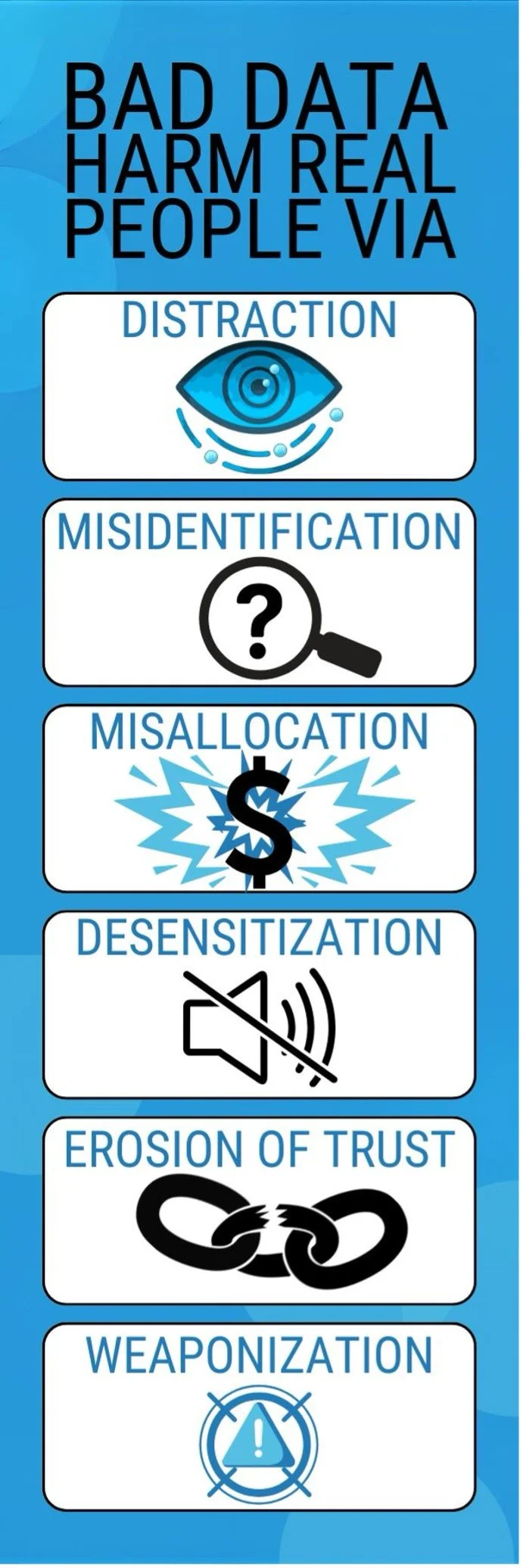

The importance of precision falls into six primary categories:

Distraction. Creating unnecessary sensationalism and distributing misinformation distracts from the horrifyingly real—though sometimes less cinematic—reality of sex trafficking. When the public is focused on conspiracy theories or exaggerated claims, attention and resources are diverted away from evidence-based interventions that could create systemic change and actually help survivors.

Misidentification. Inaccurate narratives make it difficult for the public to recognize and support victims whose experiences differ from the stereotypical image portrayed in media—which is the case for most victims. Survivors themselves may struggle to identify as victims of trafficking when their reality doesn’t match the dominant narrative. This misinformation can delay identification, block access to critical services, and perpetuate cycles of victimization.

Misallocation of Resources. Inflated or misleading numbers often drive funding and policy toward sensationalized cases rather than systemic vulnerabilities like poverty, food insecurity, housing instability, and healthcare access.9 This misdirection means fewer resources for prevention and long-term support.

Desensitization. When exaggerated claims repeatedly fail to align with reality, the public becomes skeptical and disengaged. When attention fades, advocacy campaigns lose momentum, funding dries up, and policymakers shift focus to issues that seem more urgent or credible. This creates a vacuum where trafficking persists unchecked, and survivors receive fewer resources and less support.

Erosion of Trust. While the intent behind sensational statistics is often to raise awareness, the spread of misinformation undermines credibility. In fact, when advocates exaggerate or misrepresent data, they risk damaging the credibility of the entire anti-trafficking movement—making it harder to secure funding, influence policy, and engage communities. Ethics in promotion, marketing, and fundraising are just as critical as ethics in research and direct services.

Weaponization of Data. Inaccurate statistics don’t just mislead—they can be turned into tools for harm. Inflated numbers are often used to advance political agendas, such as restricting immigration, expanding surveillance, or fueling moral panics that disproportionately impact vulnerable communities. LGBTQ+ individuals, undocumented migrants, and racial minorities often bear the brunt of these policies, facing heightened criminalization and reduced access to services. When trafficking rhetoric becomes a blunt instrument for ideology rather than a precise tool for justice, the very people most at risk of exploitation end up paying the price.

Even so, many researchers, including those who are part of the Global Association of Human Trafficking Scholars (GAHTS), are committed to advancing rigorous, ethical, and transparent research practices that strengthen—not weaken—the fight against exploitation. But the responsibility for accuracy doesn’t rest solely on researchers. Advocates, journalists, policymakers, and organizations all play a critical role in ensuring that the numbers they share are truthful, contextualized, and responsibly communicated.

PRECISION AND PROGRESS (i.e., The Good)

If bad data can distort reality and harm survivors, then good data—and responsible communication—can do the opposite. Accuracy isn’t just a research ideal; it’s an ethical obligation for everyone who shares information about trafficking. Here are several practical steps to ensure you’re disseminating accurate, trustworthy information:

Find Original Sources. Do your own fact-checking by locating the original source of any statistic. If you see a claim like “The FBI lists Atlanta as the number one city for child sex trafficking,”18 verify where the FBI actually stated that. Spoiler: They didn’t. If a statistic isn’t cited, and you cannot locate the original source, don’t believe it—and definitely don’t repeat it.

Be Specific. Once you’ve found the original source, state the context clearly. Indicate whether the number is based on national data or just one city. Specify the population referenced—adults, children, males, females, LGBTQ+ individuals—and whether it relates to labor trafficking or sex trafficking, etc. For example, a study reporting “1,000 trafficking cases” might actually mean “1,000 hotline calls,” not confirmed victims.19 Identify the exact research question and what was measured. That distinction matters. Gross overgeneralizations can be dangerous.17

Question Everything. Evaluate the methodology behind the numbers. Start with the basics:

Sample Size. Sample size matters because small samples often fail to represent the broader population, leading to skewed or unreliable results. Larger, well-selected samples generally produce more accurate and generalizable findings.

Sampling Method. Next, look at the sampling method—was it random, convenience-based, or targeted? This affects bias. Check whether key terms were clearly defined (e.g., “trafficking,” “exploitation,” or “prostitution”).15-16

Data Collection. Review the data collection process—was it self-reported, observational, or based on third-party records?

Limitations. Additionally, confirm that the study disclosed its limitations, because transparency about weaknesses signals credibility.

Ethical Safeguards. Then, consider ethical safeguards. IRB approval ensures that research involving human participants meets standards for safety, consent, and confidentiality. Studies without IRB oversight may pose risks to participants and lack accountability.

Peer-review. Lastly, verify whether the research was peer-reviewed. Peer review is a rigorous process where experts evaluate studies for correctness, clarity, and significance before publication. This filter helps ensure that only high-quality, reliable research enters the academic record. If a statistic comes from a news article, documentary, blog post, or advocacy flyer without methodological transparency, treat it with caution.

Collaborate and Cross-Verify. Don’t work in isolation. Share data with trusted partners, consult experts, and cross-check numbers against multiple reputable sources. Collaboration reduces the risk of perpetuating errors and strengthens the credibility of your message.

Avoid Sensational Framing. Even accurate numbers can be misused when presented with alarmist language or exaggerated headlines. Avoid framing that prioritizes shock value over clarity. Instead, communicate statistics in ways that inform and empower.

Be Comfortable with Ambiguity. Every study has limitations—and that’s okay. Acknowledging uncertainty is not a weakness; it’s a sign of integrity. Common limitations to trafficking research include:

Small sample sizes that make findings less generalizable;

Reliance on self-reported data, which can be influenced by memory, trauma, or fear; and

Cross-sectional designs, because the population is challenging to track across time, which is necessary to observe long-term trends.

The truth is, we may never have a perfectly accurate measurement of trafficking—its hidden nature makes that nearly impossible.20 But we can get closer than we are now by prioritizing transparency, improving methods, and resisting the temptation to oversimplify. Precision doesn’t mean pretending certainty; it means being honest about what we know, what we don’t, and what we’re still working to understand.

Sensational headlines may grab attention, but they rarely lead to meaningful change. This isn’t the Wild West, and we can’t afford to be rogue cowboys riding off with unverified numbers. If we want to dismantle the systems that enable trafficking, we need to holster the sensationalism and start with truth. Researchers, advocates, journalists, and policymakers share a collective responsibility to ensure that the numbers we use are accurate, contextualized, and ethically communicated—because when we aim for precision, the good can take center stage and real progress becomes possible.

*Survivors of commercial sexual exploitation are not considered a vulnerable population according to The Common Rule, though IRBs often employ the same considerations when reviewing research on commercial sexual exploitation.21

REFERENCES

Contrera, J. (2021). A Wayfair sex trafficking lie pushed by Qanon hurt real kids. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/interactive/2021/wayfair-qanon-sex-trafficking-conspiracy/

Kennedy, M. (2017). 'Pizzagate' gunman sentenced to 4 years in prison. National Public Radio [NPR]. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/URLs_Cited/OT2020/20-1063/20-1063-1.pdf

Furlong, C., & Hinnant, B. (2024a). Examining the intersections of family risk, foster care, and outcomes for commercially sexually exploited children. Social Sciences, 13(12), 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13120660

Furlong, C., & Hinnant, B. (2024b). Sex trafficking vulnerabilities in context: An analysis of 1,264 case files of adult survivors of commercial sexual exploitation. PLOS ONE, 19(11), e0311131. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0311131

Farrell A., & Reichert J. (2017). Using US law-enforcement data: Promise and limits in measuring human trafficking. Journal of Human Trafficking, 3(1), 39-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2017.1280324

Shively, M., Furlong, C., Ruffin, & B., Rodgers, B. (June, 2025). Measuring the magnitude and traits of local consumer demand for sex trafficking. Human Trafficking Data Conference. Southern Methodist University, University Park, TX. scholar.smu.edu/smuhtdc/

Burland, P. (2019). Still punishing the wrong people: The criminalisation of potential trafficked cannabis gardeners. In The Modern Slavery Agenda, 167-186. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781447346814.ch007

Farley, M., Cotton, A., Lynne, J., Zumbeck, S., Spiwak, F., Reyes, M.E., Alvarez, D., & Sezgin, U. (2004). Prostitution and trafficking in nine countries. Journal of Trauma Practice, 2(3–4), 33–74. https://doi.org/10.1300/J189v02n03_03

Footer, K. H., White, R. H., Park, J. N., Decker, M. R., Lutnick, A., & Sherman, S. G. (2020). Entry to sex trade and long-term vulnerabilities of female sex workers who enter the sex trade before the age of eighteen. Journal of Urban Health, 97, 406-417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00410-z

Potterat, J. J., Brewer, D. D., Muth, S. Q., Rothenberg, R. B., Woodhouse, D. E., Muth, J. B., & Brody, S. (2004). Mortality in a long-term open cohort of prostitute women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(8), 778-785. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh110

Glantz, A., Yeung, B., & Thrupkaew, N. (2025). Revealed: Trump administration retreats on combating human trafficking and child exploitation. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/sep/17/trump-human-trafficking-programs-cut

Godoy, S. M., Bellatorre, Z., Clarke, A., McClay, F., Rose, T., Rozelle-Bennett, C. C., Crisp, J., & Chapman, M. V. (2025). “This is the first time I’ve felt seen:” How community-engagement can improve human trafficking research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 24. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069251339086

The Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative [CTDC]. (2025). Global data hub on human trafficking. https://www.ctdatacollaborative.org/

Finklea, K. (2025). Criminal justice data: Human trafficking. Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R47211/R47211.3.pdf

Gerassi, L. (2015). From exploitation to industry: Definitions, risks, and consequences of domestic sexual exploitation and sex work among women and girls. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(6), 591-605. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2014.991055

Okech, D., Choi, Y. J., Elkins, J., & Burns, A. C. (2018). Seventeen years of human trafficking research in social work: A review of the literature. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(2), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1415177

Fedina, L. (2015). Use and misuse of research in books on sex trafficking: Implications for interdisciplinary researchers, practitioners, and advocates. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(2), 188-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014523337

Barnes, M. (2014). FBI speaks: Why Atlanta is No. 1 for sex trafficking, part 1. Rolling Out. https://rollingout.com/2014/04/05/fbi-atlanta-sex-trafficking/#:~:text=While%20looking%20at%20factors%20that,many%20resources%20as%20are%20available.

Polaris. (2023). U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline Statistics. https://polarisproject.org/resources/us-national-human-trafficking-hotline-statistics/

Weitzer, R. (2014). New directions in research on human trafficking. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 653(1), 6-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214521562

Protection of Human Subjects, 45 C.F.R. § 46.107(a). (2020).

About the Author

Courtney Furlong, PhD, LPC, CRC is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Huntingdon College. Her research focuses on sex trafficking and gender violence. She brings over 20 years of experience providing direct services to survivors of commercial sexual exploitation from around the world. Google Scholar